To Give Anything Less Than Your Best Is To Sacrifice The Gift

Two recent passings in the college sports play-by-play space provide an important opportunity for reflection

For this week's lesson, we're going to step away from the technical aspects of sportscasting and discuss something more fundamental: the mental approach to growing your career. Regardless of its stage, having a career in any field is a long journey filled with countless highs and lows. Even if your career is a smashing success, when you zoom in to a short window of time, you'll encounter relative valleys that can seem overwhelming if you let them be – especially if you dwell on the negative instead of seeing it within its proper perspective.

If you've spent any time in a press box, you've undoubtedly encountered people complaining about one thing or another – often people whose position you'd kill to be in. Today, I want to share a perspective that I've recently gained in the last couple of years since turning 40. If I could remember it consistently, it would change my life and prevent me from ever complaining again.

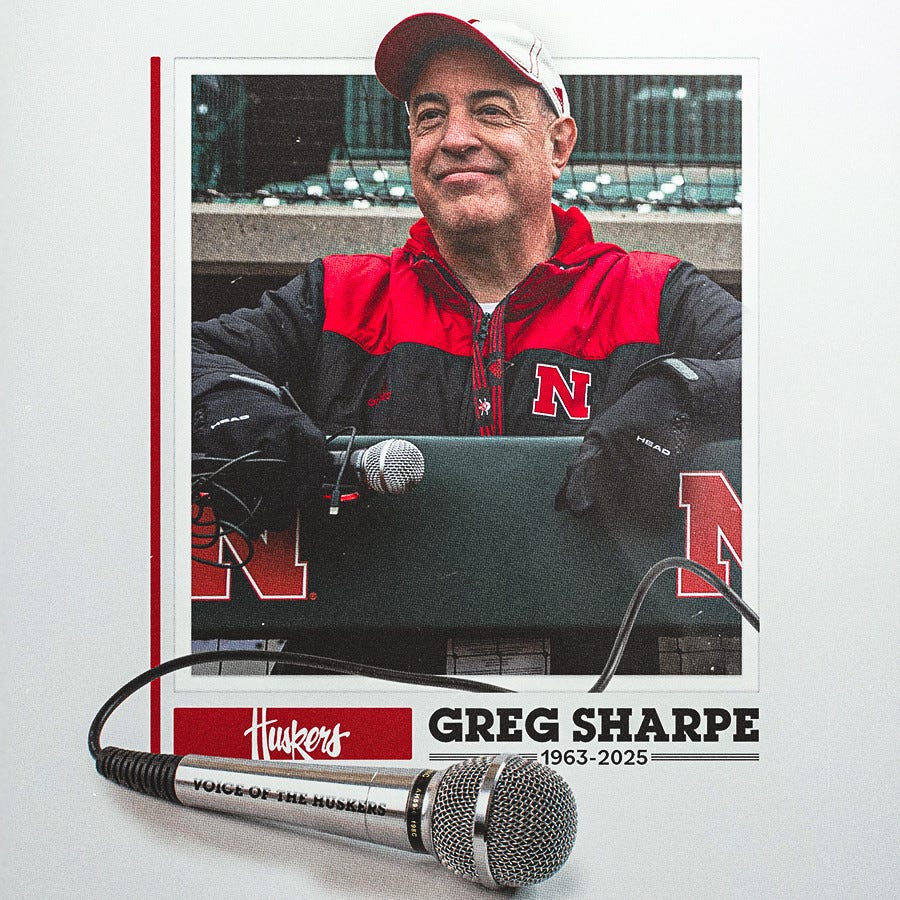

As you may have heard by now, the college sports broadcasting community has recently lost not one but two great voices and even greater men. Pete Medhurst, the play-by-play voice of the Navy Midshipmen, passed away earlier this year after a battle with brain cancer. Then, just this past Friday, Greg Sharpe, the longtime voice of Nebraska Cornhuskers football and baseball, succumbed to pancreatic cancer in his early sixties.

Early in your career, it's difficult to fully grasp this perspective unless life deals you an unusual blow. For most people in their twenties and thirties, they aren't often confronted with their own mortality face-to-face. Death seems like something far off in the distance, and time appears to have an infinite supply. But this simply isn't true. None of us is guaranteed tomorrow, let alone thousands of more tomorrows. And this is what I believe Steve Prefontaine meant with his famous quote: "To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift."

What gift was one of America's greatest and grittiest Olympic runners referring to? Was he using the word “gift” to refer to our talents? Our passion? Our potential? I believe he was talking about the simple fact that you're alive today – an absolute miracle. Not only isn't tomorrow promised to anybody, but if you think about it, none of us should even be here at all in the first place.

We don't think of life as being an utterly mind-blowing gift because we're surrounded by it. It's normal to us. We see other living people, plants, and animals everywhere we go. We're constantly reminded of life because it's all we can see: living is the default for the living. But that's only because we can't see below the surface – six feet underground. We can't see very far off into the distance, either. And because we can only see what's directly in front of us, it's pretty rare for our eyes to provide us with the proper perspective. Life is infinitely, mind-blowingly rare, small, unique, precious, and sacred. Life is a miracle.

I've only taken my appreciation for this fact to a new level in the last couple of years. My grandfather, John Castricone, passed away before I was born. I never had the opportunity to meet him, but as I've gotten older, I've become more interested in my family's history and tried to learn more about who my grandpa was and what he lived through.

His father – my great-grandfather, Antonio Castricone – immigrated to the United States in the early 1900s and brought his wife and young children with him shortly after. They had my grandpa a few years later in 1914. They settled in Columbus, Ohio, because there was a bridge that was being built there. The city needed able-bodied men, and Antonio needed work. When my grandpa was just four years old, his father lost his life in the flu epidemic of 1918. My great-grandmother, Felicia, decided to stay in America as a widow with six children, even though she didn't speak any English, simply because that's what her husband would have wanted. She trusted the reason they came to America, so she stayed with no support other than a few local government programs and her church community.

She could have returned to Italy, as would have been completely understandable, but she chose to stay. My grandpa was raised by a single mother, survived the Great Depression, and was sent off to fight in World War II. He survived a rainstorm of bullets on D-Day – many of his fellow soldiers were not so fortunate – and endured one of the most brutal winters imaginable, fighting hand-to-hand, bayonet-to-bayonet combat in the Battle of the Bulge. There is no reasonable way to assume my grandfather should have survived any of that, but he did. He came home from the war, married my grandma, they had my dad in 1949, and then my dad met my mom – and here I am.

Here's how close my life came to never happening: If my dad never meets my mom, I'm not here. And if my dad and mom don't have me, if they don't come together at the exact time in the exact way that they did, I am not here. Because out of the trillions of potential combinations of my dad's DNA and mom's DNA – all my potential brothers and sisters – there's only one combination that ends up being me. For every single one of us, it's true that if our parents had a petty fight instead of a good night nine months before our birthday, then we wouldn't be here.

If my grandpa doesn't survive all that he survived, then my dad is never here to meet my mom in the place and time that he met her. And if all my grandfather's ancestors didn't survive all that they survived long enough to procreate, then the line is broken. This isn't just true for my dad's dad, but also for my mom's dad, my dad's mom, and my mom's mom. It's true for every single person in my family line all the way back to the beginning of time. Hundreds or thousands of generations all had to go 100% in successfully procreating to get me here.

If any one of those lines breaks anywhere over the course of tens of thousands of years, there is no me. If my parents don't come together at the exact time they did, there's no me. If I don't survive to the age of 42 today, there would be no me here talking to you as we obsess over our play-by-play passion together.

Here's the thing – that's not just true for me. It's true for you too. Your stories are different, but the probability is the same. If you rewind 1,000 years, 10,000 years, 100,000 years, there is zero chance – not one in a gazillion, but 0% – that you, your life, your love, your dreams, your personality, your unique skills, could have ever happened. There's no way anyone could have hoped, wished, or expected that the trillions of events (out of trillions, at a 100 percent clip!) would come together to bring you here to this day. And yet here you are. It's a miracle – the only word we have to properly encapsulate how unlikely it is that you would be here today.

So you are alive because of an overwhelming miracle. What are you going to do about it?

Are you going to scroll through Instagram without purpose? Are you going to binge on some TV shows out of boredom? Are you going to go through the motions with your dreams because things are uncomfortably challenging? Are you going to put your head down and quit because times got a little hard? Or are you going to realize that you've been given a gift? The gift of being alive today, right here, right now where you are – and to give anything less than your best is to sacrifice that gift.

There are no guarantees in life that any of the specific things you wish for, want, or deserve will happen. Life is unfair and unjust. And while we try to arrange society to prevent those unjust things from happening as much as we can, the work will never be done. Because progress requires working together, and unfortunately, humans from rival tribes don't even like to live together, let alone work together. And even when we can make great progress with the problems of our generation, there are billions of others being born who don't understand those problems, won't necessarily agree with us on how they were solved, and will also encounter unique issues of their own. Finally, for all the information we have today to help us today, which is way more than we had a generation ago, not all of it is accurate, not all of it is measurable, and not all of the information we need is even observable. Society is messy and complicated and unfair and will always be that way. For some, the likelihood of unjust things occurring is higher than for others, and that's not fair, and it's not right.

But what can we do about it? More importantly, how are you going to respond to that fact? Are you going to get frustrated and blow up? Are you going to resent reality? Are you going to give up trying? Are you going to dwell on the negative? Or are you going to realize that the fact that you've been given this day is a radical miracle? A miracle none of us earned, none of us deserves, and today's the day that you commit to being your absolute best, giving your best not just to the world, not just to the people that you love, but giving your best to yourself.

Giving your best to yourself means absolutely emptying the tank – saying to your comfort zone, "the hell with you," saying to your fear, "the hell with you," saying to your dreams, "I'm all in," and saying to your support system, "thank you for all that you've given me so far. Let's keep going and let's do this together."

I know not everyone believes in God and people have lots of good reasons for that. But there’s a saying that “God is good.” If you read that literally, like a mathematical statement, that means God = good. So, if you don’t believe in God, can you at least believe in good? Because I personally believe that seeking God means seeking good. Seeing God means seeing good. I believe we’re called to keep our eyes fixed upon God, which is to fix them upon good. Because it’s from that spirit of positivity, of hope, of peace, of love that more good comes forth.

It means having a radical appreciation for the good in others, the good in the imperfect world, and a radical passion for the qualities of love, truth, strength, and humility themselves. I believe these four qualities serve as the ultimate litmus test for what's good:

Love is to behold something in all its imperfection and still acknowledge that it is good. Truth is to measure something and acknowledge the extent to which it aligns with reality and accuracy. Strength is to be able to execute a will against resistance. And humility is to see yourself for what you really are – both a speck of dust in this sea of other people who are all going through the same existential struggles you are, and immeasurably priceless because your valuable, meaningful life has survived and gotten here against all mathematical improbability, and because of that, you're now here to leave your unique fingerprint on the planet.

I had a broadcaster reach out to me recently because his career was in a funk and he was seeking guidance. Based on his circumstances, he didn't know what to do. I shared some of this perspective with him, and he found it helpful. So I share this today, not to be preachy, not that I know it all, but simply hoping to multiply that help across the number of people who might hear this – especially in light of the recent losses we've faced in our community at Navy and Nebraska.

To give anything other than your best is to sacrifice the gift. You've been given this day – it's an absolute miracle. What are you going to do with it?

In the most general sense possible, hopefully you put Newton's Law of Inertia to work for you: objects at rest tend to stay at rest, and objects in motion tend to stay in motion. If you've got momentum right now, great – congratulations. Enjoy it and don't take it for granted. It's hard to grab, so protect it and keep it going. Guard against complacency and use the momentum you have right now so that it can compound.

If you don't have momentum right now because you're in a funk, I'm sorry – that sucks. You're in a really hard spot because objects at rest do tend to stay at rest. Your job right now is just to create movement, create activity, get going. And do it with all the love, truth, strength and humility you can muster, toward both the profession and toward everyone you encounter in the profession. If you don't have a job calling games and you wish you had one, go call games for free. If you can't find an arena that's going to let you come in and call the game for free, then start calling the games off TV. Get yourself so good at calling games off TV that when somebody does finally let you into an arena, you crush it.

Record it. And once somebody does let you into an arena and you've got that recording, start sending that out to other places – bigger places that will let you come in and do those games to an audience of zero at first. But it'll let you create a tape with some bigger brands that makes you sound bigger and better. Use that tape to get whatever the best gig you possibly can get. Maybe that's a $50 high school game. Maybe that's just starting your own website, streaming games to an audience of single digits with no money and no revenue attached to it.

But whatever it is, remember: objects at rest tend to stay at rest, objects in motion tend to stay in motion. If you're at rest right now, if you don't have momentum, get it. Grab it. Start moving. Make it happen – because it won't be long before you're going to be at rest for good.

Rest in peace, Pete Medhurst and Greg Sharpe, forever the outstanding voices of the Navy Midshipmen and the Nebraska Cornhuskers.

Nice piece, Tony, especially the use of the Steve Prefontaine quote, “To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift”.